- Home

- Devdutt Pattanaik

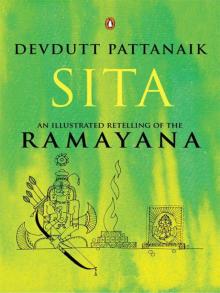

Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana

Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana Read online

Devdutt Pattanaik

SITA

An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana

Contents

Dedication

A Few Ramayana Beacons across History

A Few Ramayana Anchors across Geography

Ram’s Name in Different Scripts

Prologue: Descent from Ayodhya

1. Birth

2. Marriage

3. Exile

4. Abduction

5. Anticipation

6. Rescue

7. Freedom

Author’s Note: What Shiva Told Shakti

Epilogue: Ascent to Ayodhya

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Follow Penguin

Copyright Page

To all those who believe that the Mahabharata is more realistic

and complex than the Ramayana:

May they realize that both epics speak of dharma,

which means human potential,

not righteous conduct:

the best of what we can do

in continuously changing social contexts,

with no guarantees or certainties,

as we are being constantly and differently judged

by the subject, the object and innumerable witnesses.

In one, the protagonist is a kingmaker who can move around rules,

while in the other the protagonist is a king who must uphold rules,

howsoever distasteful they may be.

A Few Ramayana Beacons Across History

Before 2nd century BCE: Oral tellings by travelling bards

2nd century BCE: Valmiki’s Sanskrit Ramayana

1st century CE: Vyasa’s Ramopakhyan in his Mahabharata

2nd century CE: Bhasa’s Sanskrit play Pratima-nataka

3rd century CE: Sanskrit Vishnu Purana

4th century CE: Vimalasuri’s Prakrit Paumachariya (Jain)

5th century CE: Kalidasa’s Sanskrit Raghuvamsa

6th century CE: Pali Dashratha Jataka (Buddhist)

6th century CE: First images of Ram on Deogarh temple walls

7th century CE: Sanskrit Bhattikavya

8th century CE: Bhavabhuti’s Sanskrit play Mahavira-charita

9th century CE: Sanskrit Bhagavat Purana

10th century CE: Murari’s Sanskrit play Anargha-Raghava

11th century: Bhoja’s Sanskrit Champu Ramayana

12th century: Kamban’s Tamil Iramavataram

13th century: Sanskrit Adhyatma Ramayana

13th century: Buddha Reddy’s Telugu Ranganath Ramayana

14th century: Sanskrit Adbhut Ramayana

15th century: Krittivasa’s Bengali Ramayana

15th century: Kandali’s Assamese Ramayana

15th century: Balaram Das’s Odia Dandi Ramayana

15th century: Sanskrit Ananda Ramayana

16th century: Tulsidas’s Avadhi Ram-charit-manas

16th century: Akbar’s collection of Ramayana paintings

16th century: Eknath’s Marathi Bhavarth Ramayana

16th century: Torave’s Kannada Ramayana

17th century: Guru Govind Singh’s Braj Gobind Ramayana, as part of Dasam Granth

18th century: Giridhar’s Gujarati Ramayana

18th century: Divakara Prakasa Bhatta’s Kashmiri Ramayana

19th century: Bhanubhakta’s Nepali Ramayana

1921: Cinema, silent film Sati Sulochana

1943: Cinema, Ram Rajya (only film seen by Mahatma Gandhi)

1955: Radio, Marathi Geet Ramayana

1970: Comic book, Amar Chitra Katha’s Rama

1987: Television, Ramanand Sagar’s Hindi Ramayana

2003: Novel, Ashok Banker’s Ramayana series

*Dating is approximate and highly speculative, especially of the earlier works.

The Ramayana literature can be studied in four phases. The first phase, till the second century CE, is when the Valmiki Ramayana takes final shape. In the second phase, between the second and tenth centuries CE, many Sanskrit and Prakrit plays and poems are written on the Ramayana. Here we see an attempt to locate Ram in Buddhist and Jain traditions as well, but he is most successfully located as the royal form of Vishnu on earth through Puranic literature. In the third phase, after the tenth century, against the backdrop of the rising tide of Islam, the Ramayana becomes the epic of choice to be put down in local tongues. Here the trend is to be devotional, with Ram as God and Hanuman as his much-venerated devotee and servant. Finally, in the fourth phase, since the nineteenth century, strongly influenced by the European and American gaze, the Ramayana is decoded, deconstructed and reimagined based on modern political theories of justice and fairness.

The story of Ram was transmitted orally for centuries, from 500 BCE onwards, reaching its final form in Sanskrit by 200 BCE. The author of this work is identified as one Valmiki. The poetry, all scholars agree, is outstanding. It has traditionally been qualified as adi kavya, the first poem. All later poets keep referring to Valmiki as the fountainhead of Ram’s tale.

Valmiki’s work was transmitted orally by travelling bards. It was put down in writing much later. As a result, there are two major collections of this original work – northern and southern – with about half the verses in common. The general agreement is that of the seven chapters the first (Ram’s childhood) and last (Ram’s rejection of Sita) sections are much later works.

The brahmins resisted putting down Sanskrit in writing and preferred the oral tradition (shruti). It was the Buddhist and Jain scholars who chose the written word over the oral word, leading to speculation that the Jain and Buddhist retellings of Ram’s story were the first to be put down in writing in Pali and Prakrit.

Regional Ramayana s were put down in writing only after 1000 CE, first in the south by the twelfth century, then in the east by the fifteenth century and finally in the north by the sixteenth century.

Most women’s Ramayana s are oral. Songs sung in the courtyards across India refer more to domestic rituals and household issues rather than to the grand ideas of epic narratives. However, in the sixteenth century, two women did write the Ramayana: Molla in Telugu and Chandrabati in Bengali.

Men who wrote the Ramayana belonged to different communities. Buddha Reddy belonged to the landed gentry, Balaram Das and Sarala Das belonged to the community of scribes and bureaucrats and Kamban belonged to the community of temple musicians.

Keen to appreciate the culture of his people, the Mughal emperor Akbar, in the sixteenth century, ordered the translation of the Ramayana from Sanskrit to Persian, and got his court painters to illustrate the epic using Persian techniques. This led to a proliferation of miniature paintings based on the Ramayana patronized by kings of Rajasthan, Punjab, Himachal and the Deccan in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

A Few Ramayana Anchors Across Geography

* Locations not drawn to scale

Across India there are villages and towns that associate themselves with an event in the Ramayana. In Mumbai, for example, there is a water tank called ‘Banaganga’ created by the bana (arrow) of Ram.

Most Indians have heard songs and stories of the Ramayana or seen it being performed as a play or painted on cloth or sculpted on temple walls; few have read it. Each art form has its own unique narration, expression and point of view.

The earliest iconography of Ram is found in the sixth-century Deogarh temple in Uttar Pradesh established during the Gupta period. Here he is identified as an avatar of Vishnu, who in turn is associated with royalty.

The Alvars of Tamil Nadu wrote the earliest bhakti songs that refer to Ram in devotional t

erms as early as the seventh century.

In the twelfth century, Ramanuja gave bhakti (devotion) in general and Ram-bhakti in particular (devotion to God embodied as Ram) validity through Sanskrit commentaries based on the Vedanta philosophy. In the fourteenth century, Ramanand spread Rambhakti to North India. Ramdas did this in the Maharashtra region in the seventeenth century. The names Ramanuja (younger brother of Ram), Ramanand (bliss of Ram) and Ramdas (servant of Ram) indicate the value they placed on Ram.

Tibetan scholars have recorded stories from the Ramayana in Tibet since the eighth century. Similar records have been found in Mongolia in the east and Central Asia (Khotan) in the west. These probably spread via the Silk Route.

The story of Ram did spread beyond the subcontinent but had its most powerful impact in South-East Asia, where it spread via seafaring merchants who traded in fabrics and spices. These South-East Asian Ramayana s lack elements that are typically associated with the bhakti movement of India, suggesting that transmission probably took place before the tenth century CE, after which Ram became a major figure in the bhakti movement.

The Ramayana of Laos is very clearly related to Buddhism but the Thai Ramakien identifies itself as Hindu, even though it embellishes the temple walls of the Emerald Buddha in Bangkok.

From the fourteenth to the eighteenth centuries, the capital of the Thai royalty (until it was sacked) was called Ayutthaya (Ayodhya) and its kings were named after Ram.

The Ramayana continues to be part of the heritage of many South-East Asian countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia, even after they embraced Islam. So now there are stories of Adam encountering Ravana in their Ramayana s.

While it is common to refer to one Ramayana in each regional language, for example, Kamban’s in Tamil or Eknath’s in Marathi, there are in fact several dozen works in each Indian language. For example, in Odia, besides Balaram Das’s Dandi Ramayana, we have the Ramayana s of Sarala Das (Bilanka Ramayana), Upendra Bhanja (Baidehi-bilasa) and Bishwanath Kuntiya (Bichitra Ramayana).

There is a saying in Kannada that Adi Sesha, the serpent who holds the earth on its hood, is groaning under the weight of the numerous authors and poets who have retold the Ramayana.

Ram’s Name in Different Scripts

Kharoshti script 300 BCE

Ashokan Brahmi 300 BCE

Gupta Brahmi 300 CE

Kashmiri Sharada 800 CE

Kannada (Kadamba)

Telugu

Tamil

Malayalam

Odiya

Bengali

Devanagari (Hindi/Marathi)

Gurmukhi

Gujarati

Urdu

*Dating is approximate

Most scripts in India emerged from the script that we now call Brahmi.

In Jain traditions, the first Tirthankara of this era, Rishabha, passed on the first script to his daughter Brahmi.

Writing Ram’s name is a popular expression of devotion. In fact, there is a ‘Ram Ram Bank’ in Ayodhya where people even today deposit booklets of Ram’s name (Ram nam).

Though a highly evolved language, Sanskrit has no script of its own. It was written down after Prakrit, first in the Brahmi script and then in scripts such as Siddham, Sharada, Grantha which were eventually supplanted by modern scripts, most prominently Devanagari since the nineteenth century.

Prologue

Descent from Ayodhya

Blades of grass!

Ends of her hair sticking out!

That is all that was left of Sita after she had plunged into the earth. No more would she be seen walking above the ground.

The people of Ayodhya watched their king caress the grass for a long time, stoic and serene as ever, not a teardrop in his eyes. They wanted to fall at his feet and ask his forgiveness. They wanted to hug and comfort him. They had broken his heart and wanted to apologize, but they knew he neither blamed them nor judged them. They were his children, and he, their father, lord of the Raghu clan, ruler of Ayodhya, was Sita’s Ram.

‘Come, it is time to go home,’ said Ram, placing his hands on the shoulders of Luv and Kush, his twin sons.

Home? Was not the forest their home? That was where they had lived all their lives. But they did not argue with the king, this stranger, this man who they now had to call their father, who until recently had been their enemy. But their mother’s last instruction to them was very clear: ‘Do as your father says.’ They would not disobey. They too would be sons worthy of the Raghu clan.

As the royal elephant carrying the king and his two sons passed through the city gates, Hanuman, the monkey-servant of Ram, caught sight of Yama, the god of death, hiding behind the trees, looking intently at Ram. Hanuman immediately lashed his tail on the ground: a warning to the god of death not to come anywhere near the king or his family.

A frightened Yama stayed away from Ayodhya.

But Ram’s brother Lakshman did not stay away from Yama: a few days later, for some mysterious reason, Lakshman left the city and walked deep into the forest, and beheaded himself.

Hanuman did not understand. His world was crumbling: first Sita, then Lakshman. Who next? Ram? He could not let that happen. He would not let that happen. He refused to budge from the gates of Ayodhya. No one would go in, or out.

Shortly thereafter Ram lost his ring. It slipped from his finger and fell into a crack in the palace floor. ‘Will you fetch it for me, Hanuman?’ requested Ram.

Ever willing to please his master, Hanuman reduced himself to the size of a bee and slipped into the crack in the floor.

To his surprise, it was no ordinary crack. It was a tunnel, one that went deep into the bowels of the earth. It led him to Naga-loka, the abode of snakes.

As soon as he entered, he found two serpents coiling around his feet. He flicked them away. They returned with a couple more serpents. Hanuman flicked them away too. Before long, Hanuman found himself enwrapped by a thousand serpents, determined to pin him down. He gave in, and allowed them to drag him to their king, Vasuki, a serpent with seven hoods, each displaying a magnificent jewel.

‘What brings you to Naga-loka?’ hissed Vasuki.

‘I seek a ring.’

‘Oh, that! I will tell you where it is, if you tell me something first.’

‘What?’ asked Hanuman.

‘The root of every tree that enters the earth whispers a name: Sita. Who is she? Do you know?’

‘She is the beloved of the man whose ring I seek.’

‘Then tell me all about her. And tell me about her beloved. And I will point you to the ring.’

‘Nothing will give me greater joy that narrating the story of Sita and her Ram. Much of what I will tell you I experienced myself. Some I have heard from others. Within all these stories is the truth. Who knows it all? Varuna had but a thousand eyes; Indra, a hundred; and I, only two.’

All the serpents of Naga-loka gathered around Hanuman, eager to hear his tale. There is no sun or moon in Naga-loka, nor is there fire. The only light came from the seven luminous jewels on the seven hoods of Vasuki. But that was enough.

Sita has always been associated with vegetation, especially grass.

Kusha grass is a long, sharp grass that is an essential ingredient of Vedic rituals. Those performing the yagna sit on mats made of this grass and tie a ring of the grass around their finger. It is used as a torch to carry fire and as a broom to sweep the precincts. The Puranas link it to Brahma’s hair, Vishnu’s hair (when he took the form of a turtle) and Sita’s hair.

Ram belongs to the Raghu-kula or the Raghu clan. He is therefore called Raghava, he who is a Raghu, or Raghavendra, best amongst Raghus. Raghu was Ram’s great-great-grandfather and belonged to the grand Suryavamsa or the solar dynasty of kings, established by Ikshavaku and known for their moral uprightness.

Yama, the Hindu god of death, is described as a dispassionate being who does not distinguish between king and beggar when it comes to taking their life when their time on earth is up. He fears no

one but Hanuman, in popular imagination.

Hanuman is a monkey or vanara. The monkey is also a symbol of the restless human mind. He is the remover of problems (sankat mochan), feared even by death, hence the most popular guardian god of the Hindu pantheon.

Broadly, the Hindu mythic world has three layers: the sky inhabited by devas, apsaras and gandharvas; the nether regions inhabited by asuras and nagas; the earth inhabited by humans (manavas), rakshasas and yakshas. These are the lokas, or realms: Swarga-loka above, Patal-loka and Naga-loka below, and Bhu-loka – that is, earth – in the middle.

Nagas or hooded serpent beings who can take human shape are known to have jewels in their hoods. These jewels have many magical properties that enable them to grant a wish, resurrect the dead, heal the sick and attract fortune.

Traditionally, the Ramayana was always narrated in a ritual context. For example, Bhavabhuti’s eighth-century play Mahavira-charita was performed either in the temple or during the festival of Shiva.

The idea of Hanuman narrating the Ramayana is popular in folklore. It is sometimes called Hanuman Nataka.

Hanuman, the celibate monkey, is considered in many traditions to be either a form of Shiva, a son of Shiva, or Shiva himself. The nagas embody fertility, hence they are closely associated with the Goddess.

Western thought prefers to locate the Ramayana in a historical and geographical context: who wrote it, when, where? Traditional Indian thought prefers to liberate the Ramayana from the limits imposed by time and space. Ram of academics is bound to a period and place. Ram of devotees is in the human mind, hence timeless. Politicians, of course, have a different agenda.

Pregnant King

Pregnant King Devlok With Devdutt Pattanaik: 3

Devlok With Devdutt Pattanaik: 3 Devlok With Devdutt Pattanaik

Devlok With Devdutt Pattanaik Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana

Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana Olympus

Olympus Jaya: An Illustrated Retelling of the Mahabharata

Jaya: An Illustrated Retelling of the Mahabharata Brahma

Brahma