- Home

- Devdutt Pattanaik

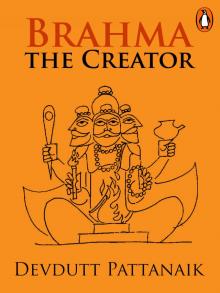

Brahma

Brahma Read online

Devdutt Pattanaik

Brahma: the Creator

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

About the Author

Praise for the Book

Dedication

Author’s Note

How to Read This Book: Author’s Recommendation

Definitions

Introduction

The Circle of Brahma and Saraswati

Glossary of Non-English Words

Bibliography

Follow Penguin

Copyright

PENGUIN BOOKS

BRAHMA: THE CREATOR

Devdutt Pattanaik writes, illustrates and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. He has, since 1996, written over 30 books and 600 columns on how stories, symbols and rituals construct the subjective truth (myths) of ancient and modern cultures around the world. His books with Penguin Random House India include The Book of Ram, Jaya: An Illustrated Retelling of the Mahabharata, Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana, The Girl Who Chose and the Devlok with Devdutt Pattanaik series, among others. He consults with corporations on leadership and governance, and TV channels on mythological serials. His TV shows include Business Sutra on CNBC-TV18 and Devlok on Epic TV. To know more, visit www.devdutt.com.

Praise for the Book

‘Folklore hasn’t been written with such simplicity, economy of words, even humour … Recommended to every kind of reader—uninitiated or expert’—First City

‘Hitch-hikers, here’s your guide to the Hindu multiverse and all the thirty-three million deities. Mythology demystified but not dumbed down. Delves for the sat behind the mithya, and isn’t heavy-handed or maudlin about it; there’s real affection in these retellings’—Tehelka

‘Who doesn’t love a good story? Devdutt Pattanaik knows that it’s a human weakness [and] his Myth=Mithya tells lots of the glorious stories that make Hinduism so endlessly fascinating’—Time Out Mumbai

To all the Gods, Goddesses, gods, goddesses,

demons and angels there are

Author’s Note

The stories in this book are my own retellings, often simplified with a great deal of poetic licence, to accommodate—without losing the essence—details from various versions of the same story found in different scriptures

No italics have been used to distinguish between English and non-English words

Capital letters have been restricted to names and titles except where explicitly stated

‘Gods’ and ‘Goddesses’ spelt with an initial capital letter need to be distinguished from ‘gods’ and ‘goddesses’ in lowercase. The former are manifestations of the infinite divine while the latter are finite forms of the divine. Shiva is God but Indra is god. Durga is Goddess but Ganga is goddess.

Sanskrit words are sometimes used as proper nouns and begin with a capital letter (for example, Maya, the Goddess who embodies delusion) and sometimes as common nouns spelt without capitals (for example, maya, delusion)

This handbook is a decoding of Hindu mythology, firm in the belief that: Within infinite myths lies the eternal truth,

Who sees it all?

Varuna has but a thousand eyes

Indra a hundred

And I, only two.

How to Read This Book:

Author’s Recommendation

You don’t have to go through this book sequentially. While that helps, you can also choose to dip into the book at random and read the captions under the illustrations and the tables and flowcharts. If you do decide to read it sequentially, do so at a leisurely pace. Take time to absorb and enjoy the ideas before you move on.

Definitions

The Hindu worldview can be startling to those accustomed to aWestern thought process, until we challenge the old definition of myth (‘the irrational, the unreasonable, the false’) and embrace a new definition (‘subjective truth expressed in stories,symbols and rituals, that shapes all cultures, Indian or Western, ancient or modern, religious or secular’). The Sanskrit word for subjective truth is mithya—not the opposite of objective truth,but a finite expression of satya, that which is infinite.

Introduction

In which the meaning of myth, its value

and expression are elaborated

Everybody lives in myth. This idea disturbs most people. For conventionally myth means falsehood. Nobody likes to live in falsehood. Everybody believes they live in truth.

But there are many types of truth. Some objective, some subjective. Some logical, some intuitive. Some cultural, some universal. Some are based on evidence; others depend on faith. Myth is truth which is subjective, intuitive, cultural and grounded in faith.

Ancient Greek philosophers knew myth as mythos. They distinguished mythos from logos. From mythos came intuitive narrations, from logos reasonable deliberations. Mythos gave rise to the oracles and the arts. From logos came science and mathematics. Logos explained how the sun rises and how babies are born. It took man to the moon. But it never explained why. Why does the sun rise? Why is a baby born? Why does man exist on earth? For answers one had to turn to mythos. Mythos gave purpose, meaning and validation to existence.

Ancient Hindu seers knew myth as mithya. They distinguished mithya from sat. Mithya was truth seen through a frame of reference. Sat was truth independent of any frame of reference. Mithya gave a limited, distorted view of reality; sat a limitless, correct view of things. Mithya was delusion, open to correction. Sat was truth, absolute and perfect in every way. Being boundless and perfect, however, sat could not be reduced to a symbol or confined to a word. Words and symbols are essentially incomplete and flawed. Sat therefore eluded communication. For communication one needs symbols and words, howsoever incomplete and flawed they may be. Through hundreds of thousands of incomplete and flawed symbols and words, it was possible to capture, or at least to indicate, the infinite perfection and boundlessness of sat. For Rishis therefore the delusion of mithya served as an essential window to the truth of sat.

Myth is essentially a cultural construct, a common understanding of the world that binds individuals and communities together. This understanding may be religious or secular. Ideas such as rebirth, heaven and hell, angels and demons, fate and freewill, sin, Satan and salvation are religious myths. Ideas such as sovereignty, nation state, human rights, women’s rights, animal rights and gay rights are secular myths. Religious or secular, all myths make profound sense to one group of people. Not to everyone. They cannot be rationalized beyond a point. In the final analysis, you either accept them or you don’t.

If myth is an idea, mythology is the vehicle of that idea. Mythology constitutes stories, symbols and rituals that make a myth tangible. Stories, symbols and rituals are essentially languages—languages that are heard, seen and performed. Together they construct the truths of a culture. The story of the Resurrection, the symbol of the crucifix and the ritual of baptism establish the idea that is Christianity. The story of independence, the symbol of the national flag and the ritual of the national anthem reinforce the idea of a nation state.

Mythology tends to be hyperbolic and fantastic to drive home a myth. It is modern arrogance to presume that in ancient times people actually believed in the objective existence of virgin births, flying horses, parting seas, talking serpents, gods with six heads and demons with eight arms. The sacredness of such obviously irrational plots and characters ensures their flawless transmission over generations. Any attempt to challenge their validity is met with outrage. Any attempt to edit them is frowned upon. The unrealistic content draws attention to the idea behind the communication. Behind virgin births and parting seas is an entity who is greater than all forces of nature put together. A god with six heads and a demon with eight arms project a universe

where there are infinite possibilities, for the better and for the worse.

From myth comes beliefs, from mythology customs. Myth conditions thoughts and feelings. Mythology influences behaviours and communications. Myth and mythology thus have a profound influence on culture. Likewise, culture has a profound influence on myth and mythology. People outgrow myth and mythology when myth and mythology fail to respond to their cultural needs. So long as Egyptians believed in the afterworld ruled by Osiris, they built pyramids. So long as Greeks believed in Charon, the ferryman of the dead, they placed copper coins for him in the mouth of the dead. Today no one believes in Osiris or Charon. There are no pyramids or coins in the mouth of the dead. Instead there are new funeral ceremonies spawned by new belief systems, new mythologies based on new myths, each one helping people cope with the painful inevitability and mystery of death.

It is ironical that for all the value we give to the rational, life is primarily governed by the irrational. Love is not rational. Sorrow is not rational. Hatred, ambition, rage and greed are irrational. Even ethics, morals and aesthetics are not rational. They depend on values and standards which are ultimately subjective. What is right, sacred and beautiful to one group of people need not be right, sacred and beautiful to another group of people. Every opinion and every decision depends on the prevailing myth. Even perfection is a myth. There is no evidence of a perfect world, a perfect man or a perfect family anywhere on earth. Perfection, be it Rama Rajya or Camelot, exists only in mythology. Yet everyone craves for it. This craving inspires art, establishes empires, sparks revolutions and motivates leaders. Such is the power of myth.

This book explores Hindu mythology. Behind the mythology is a myth. Behind the myth a truth: an inherited truth about life and death, about nature and culture, about perfection and possibility, about hierarchies and horizons. This subjective and cultural truth of the Hindus is neither superior nor inferior to other truths. It is simply yet another human understanding of life.

1

The Circle of

Brahma and Saraswati

In which the nature of the universe is explored

The circle is the most spontaneous of natural shapes, taken by the horizon, by stars, planets and bubbles. It best represents the Hindu universe because Hindus see the world as being timeless, fetterless, boundless, cyclical and infinite. This universe is the medium through which the divine presents itself; hence for Hindus every element of this universe can serve as a window to the divine.

God as creator looks like a priest, chanting Vedic hymns and holding in his four hands instruments of ritual. Every ritual is concluded with the chant ‘Shanti, shanti, shanti’, which means ‘Peace, peace, peace’. Peace is the aim of every ritual. Peace comes when one comes to terms with the three worlds: the personal world, the cultural world and the natural world. For that one needs to appreciate the world in its totality, from every point of view. That is what Brahma does with his four heads facing the four directions.

For Hindus, Brahma is God who creates the world. The world he creates is known as Brahmanda. This world is not just the outer objective world governed by mathematical principles. It is also the inner subjective world of thoughts and feelings. According to Vedic scriptures, God does not ‘create’ this world. He simply made all creatures aware of it. Awareness leads to discovery. Discovery is creation.

The world discovered by Brahma is embodied in the Goddess. She has always existed, even when no one observed her. For Brahma, the Goddess is Shatarupa, she who takes infinite forms. Shatarupa is Saraswati, goddess of knowledge, for in her infinite forms she reflects the answer to Brahma’s question: Who am I? This question is the impulse of creation. It made God open his eyes and look at the Goddess.

Saraswati is Goddess as embodiment of knowledge. She is the world that informs and inspires. She wears no jewels or cosmetics and drapes herself in a plain white sari with no desire to allure. She must be sought out. She rides a heron, the symbol of concentration, or a gander, the symbol of intellectual discrimination because it is believed to possess the ability to separate water and milk from a mixture. She holds in her four hands a lute, a book, a pen and a string of memory beads. Difficult to acquire yet eternally faithful, she is the container of all answers.

Three Hundred and Thirty Million Deities

Here we uncover the layers of divine manifestations and understand the relationships between them.

The idea of 330 million Hindu deities is a metaphor for the countless forms by which the divine makes itself accessible to the human mind.

Vishwa-rupa or Virat-Swarup is the cosmic form of God. For Hindus, God is the container of all things. All existence is a manifestation of the divine. This understanding of the world makes no room for the notion of ‘evil’. Evil means that which is devoid of Godliness. When everything is God, then nothing, not even things we despise and shy away from, can be ungodly. Good and bad are judgements based on human values. Human values—critical though they may be to establishing civilized society—are based on a limited understanding of the world. When understanding changes, values and judgements change and with them society. The Sanskrit word ‘maya’ refers to all things that can be measured. Human understanding of the world is limited, hence measurable, hence maya. To believe this maya is truth is delusion. Beyond maya, beyond human values and human judgements, beyond the current understanding of the world, is a limitless reality which makes room for everyone and everything. That reality is God.

For Hindus, all of creation is divine. Everything in nature is therefore worthy of worship. There is no discomfort visualizing God in plants, animals, rivers, mountains, rocks and in man-made objects such as pots, pans, pestles and mortars. Stories such as the one following transform rivers into molten forms of God.

Vishnu Melts

God creates the world as Brahma, sustains it as Vishnu and destroys it as Shiva. One day, Shiva started to sing. Vishnu was so moved by the melody that he began to melt. Brahma caught the molten Vishnu in a pot. This was poured on earth. It took the form of the river Ganga. The Ganga nourished the earth. To bathe in Ganga’s waters is to bathe in God. (Ganga Mahatmya)

A Hindu deity may be just a rock in a cave, a tree growing in an orchard, a river flowing down the plains, a cow wandering in the street, or perhaps an elaborately decorated idol of stone, clay or metal enshrined in a temple. Anything can be God. So long as it can respond to the human condition. In many shrines, deities are given human form merely by placing a pair of eyes and a pair of hands on a rock. Eyes represent sense organs and hands represent action organs. This indicates the deity is conscious, sensitive and responsive.

A village goddess or Grama-devi is characterized by her eyes, indicating she is sensitive to the needs of her worshippers. With an upward-pointing palm, the goddess offers emotional comfort. With a downward-pointing palm, the goddess offers material gifts. Her nose ring and bangles are a reminder that the goddess is domesticated: her power has been harnessed for the benefit of the village.

Divine sensitivity and responsiveness vary from place to place. Certain natural rock formations are found to be more potent than others. This explains why a particular set of three stones in a cave in Jammu attracts hundreds of pilgrims who identify them as the tangible manifestation of the Goddess, locally known as Vaishno-devi. Or why a particular icicle in a remote, inaccessible Himalayan cave is identified with Shiva and revered as Amarnath, the eternal lord.

Divine potency can also be a function of time. The confluence of the Ganga and the Yamuna is for Hindus more sacred than the confluence of any other rivers. Hence more pilgrims bathe at this sangam. The flow of pilgrims rises dramatically when the planet Jupiter enters the house of Aries, and the sun enters the house of Capricorn. This planetary alignment takes place once in twelve years, which is marked by the Maha Kumbha Mela, the great gathering of holy men, believed to be the largest religious congregation in the world.

It is possible, through certain prescribed rituals, t

o transform an idol into a deity, make an ordinary object of art sensitive and responsive to the human condition. In such images divine aura wanes over time, with more and more people seeking its darshan. Regular rituals performed by well-trained priests ensure the aura is replenished. To minimize loss of aura, the image is isolated in the sanctum sanctorum, a room which is rather dark, cramped and off limits to the public. Only priests who have been ritually cleansed are allowed to enter the room and touch the idol. Devotees can look upon the image from afar and that too for not more than a few minutes. Once or twice a year, during festivals, the deity or its effigy leaves the temple in a grand procession to mingle freely with the people.

For Hindus, looking at the image of God is important. This ritual act is known as darshan. During darshan the deity looks at your condition and responds to it. Thus darshan draws the transformative power of God into one’s life. Devotees of Shrinathji suffer long waits for hours in the crowded halls of his haveli in Nathdvara, Rajasthan, even though his darshan lasts for barely a few seconds, which is why it is locally known as jhanki or a teasing glimpse.

Turning for Kanakadasa

The image of Krishna in the temple at Udipi used to face the east. Only high-caste people were allowed to enter this temple. Kanakadasa, a low-caste devotee, stood outside near the western wall, desperate to catch a glimpse of the lord. To everyone’s surprise, the image in the sanctum turned west, allowing Kanakadasa to see him through a crack in the western wall. (Udipi temple lore)

Pregnant King

Pregnant King Devlok With Devdutt Pattanaik: 3

Devlok With Devdutt Pattanaik: 3 Devlok With Devdutt Pattanaik

Devlok With Devdutt Pattanaik Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana

Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana Olympus

Olympus Jaya: An Illustrated Retelling of the Mahabharata

Jaya: An Illustrated Retelling of the Mahabharata Brahma

Brahma